Miracle in the court of Miracles

The story of LEMO started in the lounge of a modest apartment above a square aptly named “La Cour des Miracles” (The Court of Miracles). It was here in 1946 that a prolific inventor decided to settle with his family and where the connector world was about to change.

Every night, in Pre-Revolution Paris, beggars returned to their slums. There, hidden from passers-by to make feel pity, they could stop pretending to be sick or handicapped. These daily “healings” earned these slums the ironic nickname of “court of miracles”, where everything seemed possible. Quite a few European cities and towns have therefore named “ Cour des Miracles ” their somewhat mysteri- ous neighbourhoods and sometimes the name stuck as the centu- ries passed, like in Morges.

Morges is a quiet little Swiss town where Léon and Hélène Mouttet settled in 1942 with Josée, their 9-year-old daughter. As a matter of fact, they decided to leave their native Jura region, neighbouring France at war, to try their luck in their adoptive town by Lake Geneva, offering a less rural and more promising life.

Léon, a precision engineer, decided to start a new life with his favour- ite hobby: by opening a small photography business.

Whether successful or not, in 1946, he decided to return to mechan- ics and to launch the production of electric contacts. The couple rented a modest apartment with an adjacent 50 m2 workshop and founded LEMO on 19th October. The place was called “ La Cour des Miracles ”, perfect to invoke Lady Luck.

During its first years, LEMO was literally a family enterprise: Léon produced components in the workshop which he assembled with Hélène at the lounge table. Their daughter Josée also gave a hand. She was 13 and had no idea she would become LEMO’s president three decades later. Nor that her son would become its third CEO.

Thanks to a special manufacturing process, LEMO proposed its contacts in the form of rivets in a single piece of molybdenum. This would ensure extraordinary resistance with hardly any wear or deformation, even after millions of operations. They equipped primarily the Swiss Post and Telecommunications (relays, contactors, call centres). Electronics (radio, television, radars) and the automotive industry (magneto switches or circuit-breakers) were also going to use them.

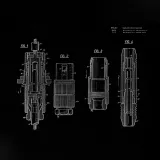

However, Léon Mouttet’s creativity did not end with simple electric contacts. His inventive mind would produce a multitude of sketches and technical drawings piling up in the family apartment. He patented and manufactured control devices for the watchmaking industry, such as dynamometers to measure the force of springs and other tools for assembling watch movements.

In 1951, the Mouttet’s hired a 38-year-old experienced lathe operator. Roland Ravay, the first LEMO employee, never left until his retirement. In the early days, there were only the two of them with Léon Mouttet in the workshop. The 50m2 included the boss’ office and some equipment: three lathes, a turning machine, a drilling, a milling and a grinding machine to prepare the tools for manufacturing. Assembly and control operations were still around the lounge table.

As years passed by, the team started to grow (a young draftsman from Basel, assembly ladies and other workers were hired). The workshop, however, did not expand and it became more and more difficult to move around among the machines.

Since Léon and Hélène, rigour and discipline have been deeply rooted at LEMO. Why spend money when in-house solutions can be used? For instance, Hélène Mouttet used a device tinkered by her husband using an old record player for deburring. To limit purchasing, the workers would readily bring their own tools from home.

Solidarity and unselfishness bonded the team. Family spirit has been another quality nurtured since the early days. Hélène Mouttet was particularly keen on keeping it up.

It was important for everyone to get on well, as the days were long and intense, as were the weeks, since Saturday was still a working day. The staff used to sing a lot in the workshop. They did so with such enthusiasm and talent that one day they made Hélène Mouttet think that she forgot to switch off the radio! Company outings were organised, such as the Watch show in Basel, to learn about the latest technologies and to imagine the tools that watchmakers would need. The staff remembered these early days with nostalgia.

As of 1954 LEMO entered the market which would make its reputation: connectors. These products were targeting the electronics market where miniaturisation, enabled by transistors, was creating new requirements.

LEMO’s “start-up” years would end in the late fifties. The company continued to develop and lack of space became critical (seven people were working in the workshop by 1960). The plans of a first real factory started to take shape. New infrastructure became even more necessary when in 1957 Léon Mouttet patented a new invention. A simple reliable interconnection system that would become an international standard and propel his enterprise among the global leaders of the connector world.